MUSTAF “A LINEAGE OF HOPE & MOTIVATION”

To quote Lin-Manuel Miranda, “Don’t forget the past can speak to the future.” For NBA veteran and University of Maryland Alumni, Jerrod Mustaf, the lineage of his past plays a huge role in his philanthropy and social responsibility in his everyday life. To understand the purpose and true calling behind the 6 foot 10 inch frame of this former NBA star, we have to dig deep into the earth’s soil and begin with his roots in Whiteville, North Carolina, where he was born and raised. Beyond his eventual fame at DeMatha Catholic High School, in Hyattsville, Maryland, beyond his individual accolades at the University of Maryland, and beyond his 11 years of playing professional basketball in the NBA and overseas, the last name of Mustaf amassed its own legacy that’s much bigger than sports.

Jerrod’s story begins in Whiteville, North Carolina where he was born and raised before moving to Maryland and eventually playing for DeMatha Catholic High School.

Jerrod was born in Whiteville, North Carolina to a family of sharecroppers. As a child he can recall getting scooped up by a truck at 5 ᴀᴍ and picking tobacco and blueberries, and eventually getting dropped off at noon. Of course, as Jerrod reflects, “This wasn’t something we wanted to do, it was a necessity and away of life for his family and many others in the south.” A lot has changed in recent times but turn the clock back 50 years, the south was a different world for African Americans. Jerrod recalled hearing a story about the patriarch of the family. “My father watched his grandfather call a six-year-old caucasian boy ‘mister’ when in public. That was very hard for my father to stomach and accept. My father went to an all black school, they didn’t have a football team (the sport of football didn’t speak to African Americans, it was nonexistent), my father experienced racism, my father’s sister was raped by a white man, and there was nothing the family could do about it during that time and era in the south.”

As Jerrod reflected on the mystic and aura of his father, he still has questions that represent the missing puzzle pieces behind the legacy of the late Shaar Mustaf. At the age of 18, Shaar moved away from Whiteville, while Jerrod, his mother, and siblings stayed in North Carolina. Jerrod vividly remembers his father, “He was like a true Black Panther, he had an afro, leather jacket, was the epitome of cool, and just so self-aware in the world we live in from an intellectual perspective. The conversations I had with him growing up when I visited him in Maryland made me realize, I had to ‘Get Out’ of Whiteville, North Carolina, and learn more about the world that was outside of the southern walls.” Present day, Jerrod mentioned he’s working on writing a book about his father and his legacy. There’s so many unknown stories he’s working tirelessly to get answers to. It’s an ongoing passion project he’s looking forward to sharing with the world and his family.

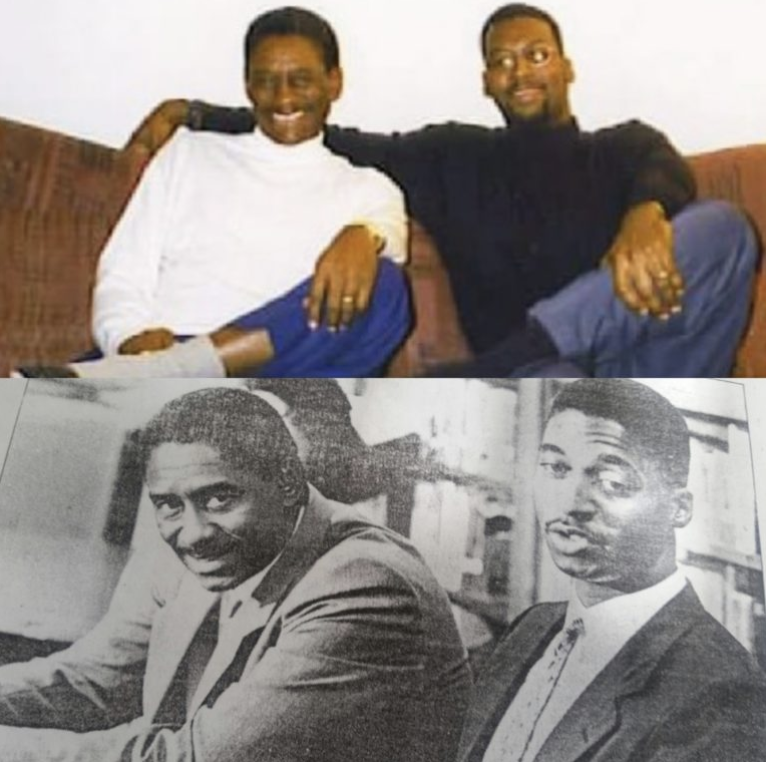

Father and Son: Shaar and Jerrod Mustaf

Jerrod and his father would periodically drive up from Maryland, where Shaar lived, to New Jersey to visit family. While in the New Jersey/New York City area, Jerrod would frequent 125th Street in Harlem to purchase books from the brothers on the streets. Jerrod recalls, “All the reading and talks with my father changed my perspective on life and the world. My father would cut out articles and I’d read the newspaper every morning. When I got home there was more articles to read and then he’d quiz me on all the current events. The books that changed my world were Message to the Black Man by Elijah Muhammed and The Autobiography of Malcolm X, written with Alex Haley. The game-changer for my father was the words, papers, and speeches of Malcolm X, which revolutionized the 60s movement and galvanized him and athletes like Muhammad Ali and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar who were socially active in their own unique way. My father was able to dedicate himself to what he believed in for the last 25 years of his remarkable life on earth.”

In the summer of 1982, Jerrod would experience his first impactful lesson of “purpose,” compliments of his father Shaar, when visiting him in Maryland. Jerrod recalls, “Growing up in North Carolina the UNC Tar Heels was my favorite college team and they just won the NCAA National Championship versus the University of Georgetown. My mother bought me a whole bunch of UNC Tar Heels apparel and I was reppin my Carolina baby blue with pride. Here I am getting off the Greyhound bus and my father takes one look at me and says, ‘You’re gonna take that off!’ He sat me down and gave me a full lecture around the history of the state of North Carolina. He broke it down layer by layer from Senator Jesse Helms, who brought aggressiveness to his conservatism and used racially charged language in his campaigns. He then shared the history of Basketball Hall of Famer, Charlie Scott being the first UNC African American athlete on scholarship, and the politics prior to that. The final point was more subjective because he made it clear that thanks to UNC, John Thompson missed out on being the first African American head coach to win a NCAA National Championship that year. The dissertation was not to belittle me but to open my eyes and my mind to the purpose of supporting a brand, versus wearing it because it’s cool or to be like others in my area who are sporting it.” The irony around that educational moment was, five years later UNC’s head basketball coach at the time, the late, Dean Smith was sitting in their living room with the Mustaf family having that same conversation. While the ACC is where Jerrod wanted to be from a familiarity standpoint and the mere fact of being close to home, the destination came down to the DC or Atlanta area. For Jerrod, both cities “were progressive cities for African Americans. There were historic civil rights movements in the state of Georgia, I loved the head coach of Georgia Tech, Bobby Cremins, and personally knew a lot of the players on the team.”

“Decisions – Decisions” – Jerrod during his junior year in high school with all the offer letters from Division I Programs.

The University of Maryland became the natural selection by Jerrod but he had a few caveats before they could get a commitment from him. The foundation for the University of Maryland started with the Basketball Hall of Famer, Charles ‘Lefty’ Driesell who established a relationship with Jerrod when he was in the 9th grade. Jerrod often found himself with his friends playing at the University of Maryland gymnasium thanks to Lefty giving them access. He crossed paths with Maryland greats like Adrian Branch and the late Len Bias. Jerrod shared that “Being around those guys made me realize how much harder I had to work to achieve the talent and success of those University of Maryland basketball elites. On the flip side, playing against them gave me the confidence to compete against the teens my age with no problem.

“During the recruitment process, I had the pleasure of meeting John Slaughter, who was the first African American Chancellor in the ACC with the University of Maryland. The other piece to the puzzle was the relationship and respect my family had with University of Maryland Head Coach Bob Wade. Bob was relatable, had shared experiences, and he understands the inner city because he coached at Dunbar High School for 10 years and amassed a record of 341 wins and only 24 loses. In his best two seasons at the inner-city high school, 1981–1983, Wade put together teams that produced a 60-0 record, headlined by names like Muggsy Bogues, Reggie Williams, David Wingate, and the late Reggie Lewis. As an added bonus, my parents built a rapport with Bob and his wife. From a socially conscious side, I was talking to the University of Maryland about allowing a group of students from the inner city to come to the games. This was especially for the kids that couldn’t financially afford to attend the games but loved hoops. In college, I had no issue with speaking up or being an advocate for the student athletes. As a family, we received hate mail and have been called a racist family. The media stayed all over us to ask questions that would lead to more stories, and controversy around what we stood for. At times a lot of what we shared was taken out of context by the writers. My time at the University of Maryland became very political and while I had great success my sophomore year, I gave up my final two years of eligibility and entered the NBA Draft in 1990.”

In the summer of 1990, Jerrod was the 17th pick in the first round of the NBA Draft by the New York Knicks. For Jerrod, the wake-up call of going from being one of the best college basketball players in the country to being just one of the guys on a NBA roster was a rude awakening. Jerrod reflected on his rookie year, “I was by far one of the youngest rookies coming into the league that was filled with nothing but grown men. Present-day in the NBA, even if you enter the league at 19, there’s a good chance you played against most of the stars that are 25 years old and considered NBA vets. When I joined the Knicks I played with Maurice Cheeks, who won a championship in Philly; Kiki Vandeweghe, who was a tremendous veteran and scorer whose basketball camp I attended; and then there was the big man Patrick Ewing, who I knew very well from watching the epic clash between Georgetown and UNC. One of my greatest teammates of all time was Charles Oakley. He brought his blue-collar mentality to the hardwood every single night, and his role was the reverse of the quintessential superstar. His job quite simply was to make the superstars better. Oak made sacrifices to make Patrick Ewing’s life easier and it was a trade-off because there were things that Patrick did to back Oak on the hardwood as well.”

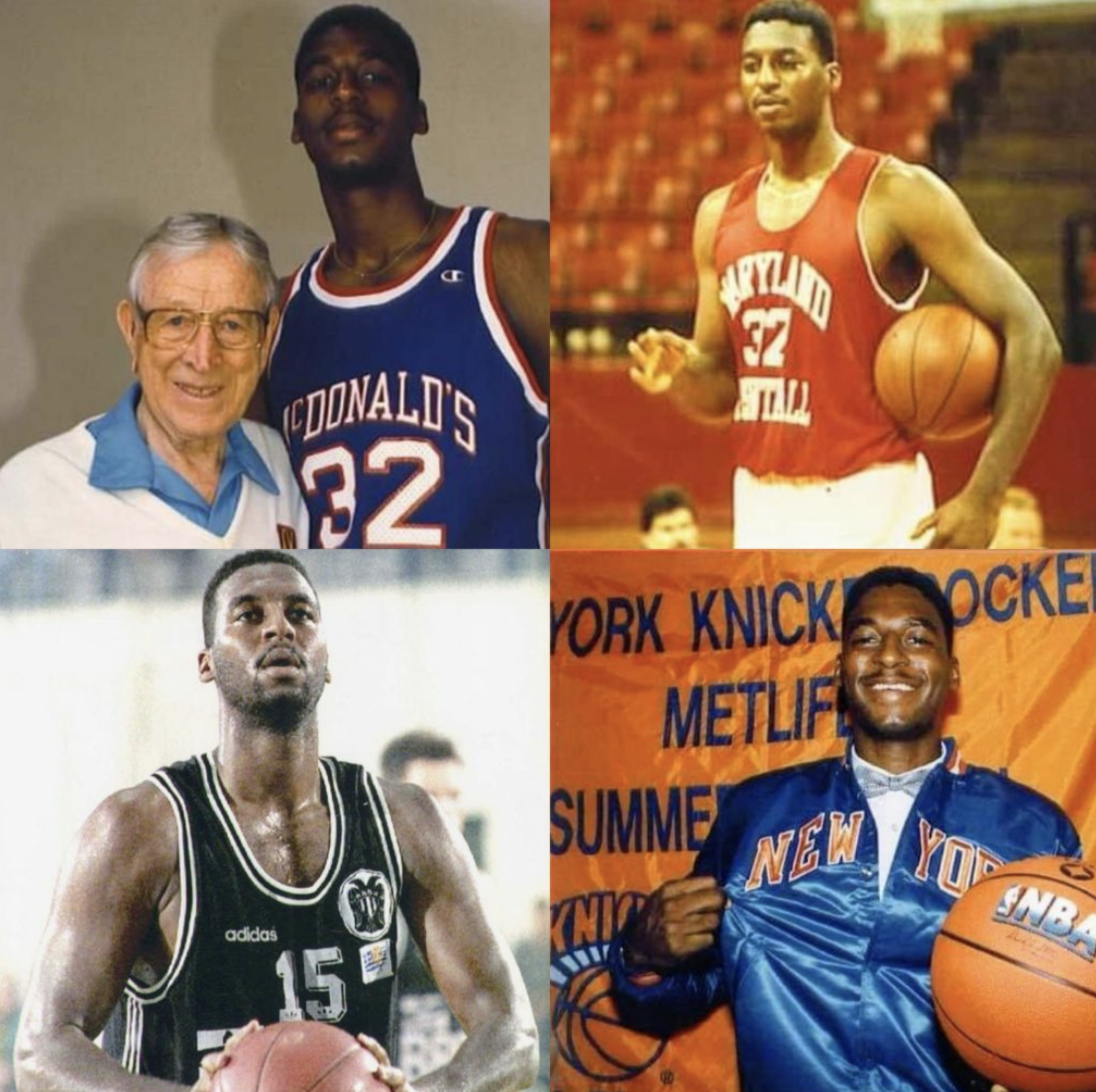

Basketball Journey – Jerrod Mustaf through the years – high school, college, and to the pros.

The league in the 90s was a reality check for Jerrod. As a rookie, he knew he could shoot better and outplay certain bench reserves he’d match up against. When he’d check into the game, the perception of what played out in his head didn’t match the reality of what took place on the court. Jerrod shared, “I’d get into games and night in and night out I found myself being matched up against grown men that had no sympathy for rookies, they know their role, know their position, and embody the expression a ‘pros-pros.’ Then there were the elite superstars where one night it was Larry Bird and Kevin McHale with the Boston Celtics, the next night was against Dominique Wilkins and the Atlanta Hawks, and when you go west you had to deal with Karl Malone and John Stockton running multiple variations of the pick and roll all night. Even the veterans that were later in their career, such as the late Moses Malone, was still a monster to deal with. The basketball IQ and efficiency of these players were top-notch and humbling to experience. It takes time to understand the discipline, find your niche, master your timing, and be aligned with the right opportunity and coach.

Beyond the Xs and Os, there’s the mental aspect to the game. For example one night you end up playing two to three minutes versus the Lakers and get benched, never to get back in the game again. As a young athlete your mind goes all over the map where you start doubting yourself, questioning your ability to play in the NBA. As a general statement, it can lead to athletes diverting their sorrows into something else like blowing off steam by excessively lifting weights, drinking, blowing money on materialistic things, or just finding oneself on edge and arguing with your coaches and the general manager. It’s a tough pill to swallow because everything is on display, where you are considered a loser not behind closed doors but in public on national TV or in front of a live audience. I’ll never forget as a Knick, Coach Stu Jackson telling me in a direct and serious tone ‘You don’t shoot jumpers.’ and from that point forward it made me hesitate and overthink the idea of taking jump shots, which was second nature to me my whole life. When a coach believes in you, that holds a lot of weight for your confidence and approach to the game. My final year in the league I didn’t care, whenever I touched the ball I was looking to score and took on a ‘I have nothing to lose’ mentality.”

Later in his career, from 1991–94, Jerrod would play for the Phoenix Suns. In the NBA Finals versus Michael Jordan and the eventual NBA Finals Champions the Chicago Bulls. Jerrod’s minutes were limited and somewhat nonexistent. Jerrod recalls, “I remember chatting with Scott Williams of the Bulls and he asked me ‘Why aren’t you playing? I know you can play, I’ve seen you in college.’ On the Suns there was a pecking order and it started with the best player on the team, Charles Barkley being the #1 guy, and then as a position player, they had a true seasoned veteran in Tom Chambers backing him up and I would just watch from the bench waiting for my turn.” While Jerrod’s NBA career was not the storybook ending or narrative he envisioned, the takeaways from his years as a pro would later play a role in his everyday purpose in life.

Life after the NBA was a transition that took Jerrod to Europe where he continued his professional career. Jerrod recalls, “My career after the NBA brought me to Spain where I learned a lot about myself and elements of the game from one of the best coaches of all time, Alejandro ‘Aito’ Garcia Reneses. Coach taught me patience, how to slow the game down, and how to see the game for what it is. Beyond the game, he encouraged me to explore Europe through sightseeing, understand the culture better, and recommended books to read. When I played overseas for him, it was a shared experience with passing, timing, team concept versus individual accomplishments, sacrifice, and making your teammates better through leadership.” An athlete’s professional career will eventually come to a close, so enjoy it while it lasts but, most importantly, realize it only represents several chapters of your life and not your entire legacy on earth.

As Jerrod was leaving college in 1990, Jerrod and his father created the nonprofit program Take Charge Juvenile Diversion Program Inc. (Take Charge Program), which is still based in the Maryland/DC area. The program was founded as a diversion program, where they took inner-city kids from the court systems and detention centers and enrolled them in the program to turn their lives around and provide hope. Present-day, the program is centered around youth resistance to avoid negative behaviors and actions by the youth in the inner cities of Maryland and DC. Jerrod shared, “The public schools might not have the background with behavior and social concerns. Our program allows the public schools to focus on the educational layers, where we handle the other social and life skills components. To incorporate sports, we use basketball to complement the program and engage the youth enrolled. Each year, the number of students that don’t go to class or get discouraged from being cut from the basketball team in November is a real thing. It’s one of the main reasons I created the basketball component to my Take Charge Program, to provide hope and a second chance for all.

“While the Take Charge Program represents my hometown on the east coast, I had something unique out west back in the 90s. On the west coast during my playing career in Phoenix, I opened a Black Bookstore, that became the meeting spot and melting pot of the community. Throughout my career, I had two entities that were near and dear to me between the store in the west coast and the Take Charge Program I’d return to in the off-season back east.”

Take Charge Program – A tradition of excellence and continued legacy for 28 years and beyond.

As for what’s next for the Take Charge Program, Jerrod has a vision and a destination he’d like to see the program evolve into. The most important was ensuring sustainability as an organization so that funding is available to give back. The program has run a variety of annual programs for girls and boys. For the girls, their program “Just for Her” encouraged self love, self sufficiency, and sisterhood. Some of the other programs centered around the themes of “Women empowerment,” “Leadership and Steam,” “Pregnancy Prevention,” and “Engineering/Arts and Math” to name a few. For the boys, they piloted a “Adult Re-Entry Program” and a “Fatherhood for young adults program” providing life skills and shared resources around how to become better fathers. In between all of this, Jerrod is actively involved in grant writing to fund these programs. The constant challenge is that one year there’s funding available for a select program and then the next year the program has to pivot and change directions based on the available grant funding out there.

A long-term goal is being able to replicate his program in other states and cities. In order to make that vision a reality, it will take the right people to administer and see it through. Present day, it’s something Jerrod is formalizing and road mapping but it’s still a long term-goal for the organization. Jerrod shared, “All of this wouldn’t be possible if it wasn’t for my father Shaar who started this program with me to remind me of our civic duty and responsibility as a citizen to give back to society. A special shout of gratitude to the administrative team that has historically been a part of the program. In addition I’d like to thank my current team that comprises the Take Charge Program for everything you do. They play a huge role behind the scenes in the programming, facilitation, and administration year round. For 28 years and counting, our contribution to my community is not something that makes the news every day but the butterfly effect of the positivity it has produced in this world is all the fulfillment I live for.”

“All of this wouldn’t be possible if it wasn’t for my father Shaar who started this program with me to remind me of our civic duty and responsibility as a citizen to give back to society.”

Jerrod shared a personal story that put a stamp on the purpose of why the Take Charge Program is so near and dear to him. “I remember taking my grandson to the barbershop and there were a couple of young guys in there looking at me and eventually asked me, ‘Are you Mustaf?’ ‘Related to Shaar Mustaf?’ When I replied ‘yes, that’s my father.’ The young men proceeded to talk about the program and one of them mentioned, ‘My whole life people would tell me I was a bad kid. Mr. Mustaf would always take the time to tell me something positive about myself to keep my spirits up and keep me determined to not listen to the masses and negativity.’ Here I am many years later, listening to these young men that have been impacted by my father’s legacy and seeing them cut my grandson’s hair. That alone made me realize the higher purpose of impact and legacy of my father’s dream with this program. Everything truly came full circle that afternoon and really touched me and reinforced the importance of being there for this next generation that might be missing a father figure, doesn’t have a family, or just needs someone to believe in them.”

The legacy and continued tradition of basketball lives on with the Mustaf family. Jerrod’s daughter, Imani Mustaf, is a freshman student-athlete at the University of Richmond playing for their women’s basketball team. His 13-year-old son, Jaeden Mustaf, is a nationally ranked middle school basketball scholar athlete. His daughter Terah has been an assistant coach for Eleanor Roosevelt High School girls basketball team and has won two state championships coaching and one as a player. To round out the rest of his family, his children, Ashley, Jakarrea, Amira, Jerrod II, and Shaar Ramadan II are pursuing other avenues in life to build on the family legacy. Jerrod is a proud father and loves his family with all his heart.

“As a father, I want my children to see my contribution to society. I want to be known for my reputation in the community and positivity my program is creating. My present day is much bigger than my professional sports career…”

For Jerrod, his continued legacy on earth is inspired by his lineage, his upbringing, his father who challenged him to see the world from a macro level, his college experience that saw triumphs and adversity, and his NBA and FIBA professional basketball career that prepared him for his next calling in life. Jerrod believes, “As a father, I want my children to see my contribution to society. I want to be known for my reputation in the community and the positivity my program is creating. My present day is much bigger than my professional sports career and rightly deserves to hold more weight and value. Not a day goes by where I walk into a public establishment or just going about my day and someone stops me to ask, ‘Did you play basketball?’ I have a lot to offer the game of basketball with all my life experiences and knowledge from being a former professional athlete. I love to mentor, give back, and merge hoops with inspiration. By doing so, it provides the best of both worlds of education and sports. Social media platforms shouldn’t be raising your children, it won’t enable them to be better human beings. The world needs more real life role models in their own respective communities impacting the youth of America. My father always reinforced that it’s not about ‘me’ but about ‘we.’ My individual accolades, newspaper clippings, and the notoriety of being a bigger than life athlete to the public represents memorable chapters I’ll never forget. When it’s all said and done, my true calling in life is all about enriching lives and inspiring a future generation of leaders to believe in themselves and love themselves unconditionally. My father always told me, ‘Your name is everything! Make sure you take care of it.’ I know he’s with me every day in spirit and gives me the strength and continued faith to make a difference in this world and bring grace and honor to the name Mustaf.

To learn more about the “Take Charge Program” and the “Take Charge Pride Basketball,” feel free to follow on social media. The program is always looking for new partners, donations, and sponsors to support their programming and mission.